Aga Khan delivers Ogden Lecture March 10, 2014 at Brown Univ

Aga Khan delivers Ogden Lecture March 10, 2014 at Brown Univ

February 17, 2014 | Media Contact: Courtney Coelho | 401-863-7287

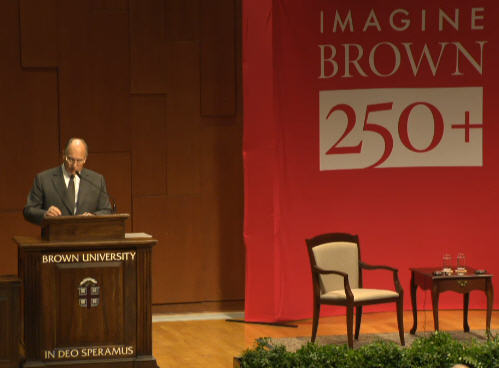

His Highness the Aga Khan will deliver a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs at Brown University on Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m. His lecture will be given as part of Brown’s 250th anniversary celebration and will be carried live on the Brown website.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — His Highness the Aga Khan will deliver a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs at Brown University on Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m. His lecture will take place in Salomon Center for Teaching, De Ciccio Family Auditorium, and will be given as part of Brown's 250th anniversary celebration.

This is a ticketed event, open to Brown University students, faculty and staff. Tickets can be reserved online starting Monday, Feb. 17, 2014.

The lecture will also be presented live online at www.brown.edu/web/livestream/.

Editors: Credentials are required for this event. To register, contact Courtney Coelho at courtney_coelho@brown.edu or 401-863-7287 by March 4, 2014.

Who

His Highness the Aga Khan, founder and chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), is the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. In the context of his hereditary responsibilities, His Highness has been deeply engaged with the development of Asia and Africa for more than 50 years.

The Aga Khan has received numerous honorary degrees and awards in recognition of his work including, in the United States, the University of California–San Francisco Medal as well as the ULI J.C. Nichols Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development. In addition, Harvard University and Brown University conferred honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) degrees in 2008 and 1996, respectively.

More information about the Aga Khan can be found on the Ogden Lecture site.

What

The 88th Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs, which will be given as part of Brown's 250th anniversary celebration.

Where

Salomon Center for Teaching, De Ciccio Family Auditorium, the College Green

When

Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m.

The Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture

Since 1965, the Ogden Lectureship has presented the University and its neighboring communities with authoritative and timely addresses about international affairs. The lectureship was established in memory of Stephen A. Ogden Jr., a member of the Brown Class of 1960, who died in 1963 from injuries he suffered in a car accident during his junior year. His family created the series as a tribute to Ogden’s interest in advancing international peace and understanding.

Dozens of heads of state, diplomats, and observers of the international scene have participated in the series, including Queen Noor of Jordan, former President of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev, President of Brazil Fernando Henrique Cardoso, former Canadian Prime Minister Kim Campbell, media innovator Ted Turner, astronaut Sen. John Glenn, economist Paul Volcker, Bolivian President Evo Morales, and Romano Prodi, former prime minister of Italy.

Editors: Brown University has a fiber link television studio available for domestic and international live and taped interviews, and maintains an ISDN line for radio interviews. For more information, call (401) 863-2476.

Providence, Rhode Island 02912, USA

Phone: 401-863-1000

Maps & Directions / Contact Us

© 2014 Brown University

His Highness the Aga Khan will deliver a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs at Brown University on Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m. His lecture will be given as part of Brown’s 250th anniversary celebration and will be carried live on the Brown website.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — His Highness the Aga Khan will deliver a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs at Brown University on Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m. His lecture will take place in Salomon Center for Teaching, De Ciccio Family Auditorium, and will be given as part of Brown's 250th anniversary celebration.

This is a ticketed event, open to Brown University students, faculty and staff. Tickets can be reserved online starting Monday, Feb. 17, 2014.

The lecture will also be presented live online at www.brown.edu/web/livestream/.

Editors: Credentials are required for this event. To register, contact Courtney Coelho at courtney_coelho@brown.edu or 401-863-7287 by March 4, 2014.

Who

His Highness the Aga Khan, founder and chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), is the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. In the context of his hereditary responsibilities, His Highness has been deeply engaged with the development of Asia and Africa for more than 50 years.

The Aga Khan has received numerous honorary degrees and awards in recognition of his work including, in the United States, the University of California–San Francisco Medal as well as the ULI J.C. Nichols Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development. In addition, Harvard University and Brown University conferred honorary Doctor of Laws (LL.D.) degrees in 2008 and 1996, respectively.

More information about the Aga Khan can be found on the Ogden Lecture site.

What

The 88th Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs, which will be given as part of Brown's 250th anniversary celebration.

Where

Salomon Center for Teaching, De Ciccio Family Auditorium, the College Green

When

Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m.

The Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture

Since 1965, the Ogden Lectureship has presented the University and its neighboring communities with authoritative and timely addresses about international affairs. The lectureship was established in memory of Stephen A. Ogden Jr., a member of the Brown Class of 1960, who died in 1963 from injuries he suffered in a car accident during his junior year. His family created the series as a tribute to Ogden’s interest in advancing international peace and understanding.

Dozens of heads of state, diplomats, and observers of the international scene have participated in the series, including Queen Noor of Jordan, former President of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev, President of Brazil Fernando Henrique Cardoso, former Canadian Prime Minister Kim Campbell, media innovator Ted Turner, astronaut Sen. John Glenn, economist Paul Volcker, Bolivian President Evo Morales, and Romano Prodi, former prime minister of Italy.

Editors: Brown University has a fiber link television studio available for domestic and international live and taped interviews, and maintains an ISDN line for radio interviews. For more information, call (401) 863-2476.

Providence, Rhode Island 02912, USA

Phone: 401-863-1000

Maps & Directions / Contact Us

© 2014 Brown University

Last edited by Admin on Tue Mar 11, 2014 1:45 am, edited 1 time in total.

brown.edu/campus-life/events/ogden/his-highness-aga-khan

His Highness the Aga Khan

His Highness the Aga Khan, founder and chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), is the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. In the context of his hereditary responsibilities, His Highness has been deeply engaged with the development of Asia and Africa for more than 50 years.

The AKDN is a group of private, international, non-denominational agencies working to improve living conditions and opportunities for people in specific regions of the developing world. The Network’s organisations have individual mandates that range from healthcare (through over 400 health facilities including 13 hospitals) and education (with over 200 schools) to architecture, rural development, the built environment and the promotion of private-sector enterprise. Together, they work towards a common goal — to build institutions and programmes that can respond to the challenges of social, economic and cultural change on an on-going basis.

AKDN’s social development agencies include Aga Khan Health Services, Aga Khan Planning and Building Services, Aga Khan Education Services, Aga Khan Academies, Aga Khan Agency for Microfinance, Aga Khan Foundation, Focus Humanitarian Assistance as well as two universities, the Aga Khan University (with 5 campuses and 3 teaching sites) and the University of Central Asia (whose School of Professional and Continuing Education has served close to 50,000 students in Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan). The Aga Khan Trust for Culture co-ordinates AKDN’s cultural activities, including the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme, Aga Khan Music Initiative, Aga Khan Museum, the on-line archive Archnet.org, and the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture (at Harvard and MIT). The Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development (AKFED) is dedicated to building commercially viable enterprises — in tourism, banking, insurance, media, aviation, industry and infrastructure — in the developing world.

The Network works in 30 countries. It employs approximately 80,000 people, the majority of whom are based in developing countries, and has an annual budget for non-profit development activities of approximately US$ 600 million. In 2012, AKFED’s project companies generated close to $3b in total revenue — surpluses of which are all reinvested in further development activities. The AKDN enjoys close partnerships with public and private institutions, including amongst others, governments, international organisations, companies, foundations, and universities.

The Aga Khan, the AKDN and the Ismaili community have had long-standing ties to the United States. Among these are Agreements of Cooperation with the States of Texas, California and Illinois, which establish a framework for collaboration around issues of mutual interest that advance the human condition and better cross cultural understanding as well as partnerships with the United States Government in Central Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

The Aga Khan has received numerous honorary degrees and awards in recognition of his work including, in the United States, the University of California San Francisco Medal as well as the ULI J.C. Nichols Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development. In addition, Harvard University and Brown University conferred honorary Doctor of Law degrees upon His Highness in 2008 and 1996, respectively.

His Highness the Aga Khan

His Highness the Aga Khan, founder and chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), is the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. In the context of his hereditary responsibilities, His Highness has been deeply engaged with the development of Asia and Africa for more than 50 years.

The AKDN is a group of private, international, non-denominational agencies working to improve living conditions and opportunities for people in specific regions of the developing world. The Network’s organisations have individual mandates that range from healthcare (through over 400 health facilities including 13 hospitals) and education (with over 200 schools) to architecture, rural development, the built environment and the promotion of private-sector enterprise. Together, they work towards a common goal — to build institutions and programmes that can respond to the challenges of social, economic and cultural change on an on-going basis.

AKDN’s social development agencies include Aga Khan Health Services, Aga Khan Planning and Building Services, Aga Khan Education Services, Aga Khan Academies, Aga Khan Agency for Microfinance, Aga Khan Foundation, Focus Humanitarian Assistance as well as two universities, the Aga Khan University (with 5 campuses and 3 teaching sites) and the University of Central Asia (whose School of Professional and Continuing Education has served close to 50,000 students in Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan). The Aga Khan Trust for Culture co-ordinates AKDN’s cultural activities, including the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, Aga Khan Historic Cities Programme, Aga Khan Music Initiative, Aga Khan Museum, the on-line archive Archnet.org, and the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture (at Harvard and MIT). The Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development (AKFED) is dedicated to building commercially viable enterprises — in tourism, banking, insurance, media, aviation, industry and infrastructure — in the developing world.

The Network works in 30 countries. It employs approximately 80,000 people, the majority of whom are based in developing countries, and has an annual budget for non-profit development activities of approximately US$ 600 million. In 2012, AKFED’s project companies generated close to $3b in total revenue — surpluses of which are all reinvested in further development activities. The AKDN enjoys close partnerships with public and private institutions, including amongst others, governments, international organisations, companies, foundations, and universities.

The Aga Khan, the AKDN and the Ismaili community have had long-standing ties to the United States. Among these are Agreements of Cooperation with the States of Texas, California and Illinois, which establish a framework for collaboration around issues of mutual interest that advance the human condition and better cross cultural understanding as well as partnerships with the United States Government in Central Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

The Aga Khan has received numerous honorary degrees and awards in recognition of his work including, in the United States, the University of California San Francisco Medal as well as the ULI J.C. Nichols Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development. In addition, Harvard University and Brown University conferred honorary Doctor of Law degrees upon His Highness in 2008 and 1996, respectively.

Brown University

02/17/2014 | Press release

Aga Khan to deliver Ogden Lecture March 10

distributed by noodls on 02/17/2014 12:52

His Highness the Aga Khan will deliver a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. '60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs at Brown University on Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m. His lecture will be given as part of Brown's 250th anniversary celebration and will be carried live on the Brown website.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] - His Highness the Aga Khan will deliver a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. '60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs at Brown University on Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m. His lecture will take place in Salomon Center for Teaching, De Ciccio Family Auditorium, and will be given as part of Brown's 250th anniversary celebration.

This is a ticketed event, open to Brown University students, faculty and staff. Tickets can be reserved online starting Monday, Feb. 17, 2014.

The lecture will also be presented live online at www.brown.edu/web/livestream/.

Editors: Credentials are required for this event. To register, contact Courtney Coelho at courtney_coelho@brown.edu or 401-863-7287 by March 4, 2014.

Who

His Highness the Aga Khan, founder and chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), is the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. In the context of his hereditary responsibilities, His Highness has been deeply engaged with the development of Asia and Africa for more than 50 years.

The Aga Khan has received numerous honorary degrees and awards in recognition of his work including, in the United States, the University of California-San Francisco Medal as well as the ULI J.C. Nichols Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development. In addition, Harvard University and Brown University conferred

noodls.com/view/61A9E33F2002F6DC82EB1B622A709957360E92AF?5259xxx1392663850dpufdpuf#sthash.dr7jSioQ.dpuf

02/17/2014 | Press release

Aga Khan to deliver Ogden Lecture March 10

distributed by noodls on 02/17/2014 12:52

His Highness the Aga Khan will deliver a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. '60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs at Brown University on Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m. His lecture will be given as part of Brown's 250th anniversary celebration and will be carried live on the Brown website.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] - His Highness the Aga Khan will deliver a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. '60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs at Brown University on Monday, March 10, 2014, at 5 p.m. His lecture will take place in Salomon Center for Teaching, De Ciccio Family Auditorium, and will be given as part of Brown's 250th anniversary celebration.

This is a ticketed event, open to Brown University students, faculty and staff. Tickets can be reserved online starting Monday, Feb. 17, 2014.

The lecture will also be presented live online at www.brown.edu/web/livestream/.

Editors: Credentials are required for this event. To register, contact Courtney Coelho at courtney_coelho@brown.edu or 401-863-7287 by March 4, 2014.

Who

His Highness the Aga Khan, founder and chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), is the 49th hereditary Imam (spiritual leader) of the Shia Ismaili Muslims. In the context of his hereditary responsibilities, His Highness has been deeply engaged with the development of Asia and Africa for more than 50 years.

The Aga Khan has received numerous honorary degrees and awards in recognition of his work including, in the United States, the University of California-San Francisco Medal as well as the ULI J.C. Nichols Prize for Visionaries in Urban Development. In addition, Harvard University and Brown University conferred

noodls.com/view/61A9E33F2002F6DC82EB1B622A709957360E92AF?5259xxx1392663850dpufdpuf#sthash.dr7jSioQ.dpuf

As received

Mawlana Hazar Imam arrived in the United States on the afternoon of Sunday, March 9, 2014. Mawlana Hazar Imam was received at the airport in Providence, Rhode Island by the Chairman of the Leaders’ International Forum, Dr. Mahmoud Eboo, and President of the Council for USA, Dr. Barkat Fazal.

Mawlana Hazar Imam has been invited by the President of Brown University, Dr. Christina Paxson, to deliver the prestigious Ogden Lecture at Brown on Monday, March 10, 2014.

Mawlana Hazar Imam arrived in the United States on the afternoon of Sunday, March 9, 2014. Mawlana Hazar Imam was received at the airport in Providence, Rhode Island by the Chairman of the Leaders’ International Forum, Dr. Mahmoud Eboo, and President of the Council for USA, Dr. Barkat Fazal.

Mawlana Hazar Imam has been invited by the President of Brown University, Dr. Christina Paxson, to deliver the prestigious Ogden Lecture at Brown on Monday, March 10, 2014.

Do you know what time the speech is? Is it 5PM EST, or am I mistaken?Admin wrote:As received

Mawlana Hazar Imam arrived in the United States on the afternoon of Sunday, March 9, 2014. Mawlana Hazar Imam was received at the airport in Providence, Rhode Island by the Chairman of the Leaders’ International Forum, Dr. Mahmoud Eboo, and President of the Council for USA, Dr. Barkat Fazal.

Mawlana Hazar Imam has been invited by the President of Brown University, Dr. Christina Paxson, to deliver the prestigious Ogden Lecture at Brown on Monday, March 10, 2014.

providencejournal.com/breaking-news/content/20140310-muslim-leader-the-aga-khan-to-speak-at-brown-monday-evening.ece

Muslim leader the Aga Khan to speak at Brown Monday evening

March 10, 2014 04:21 PM

0 7 +10 0 0 0

By Philip Marcelo

pmarcelo@providencejournal.com

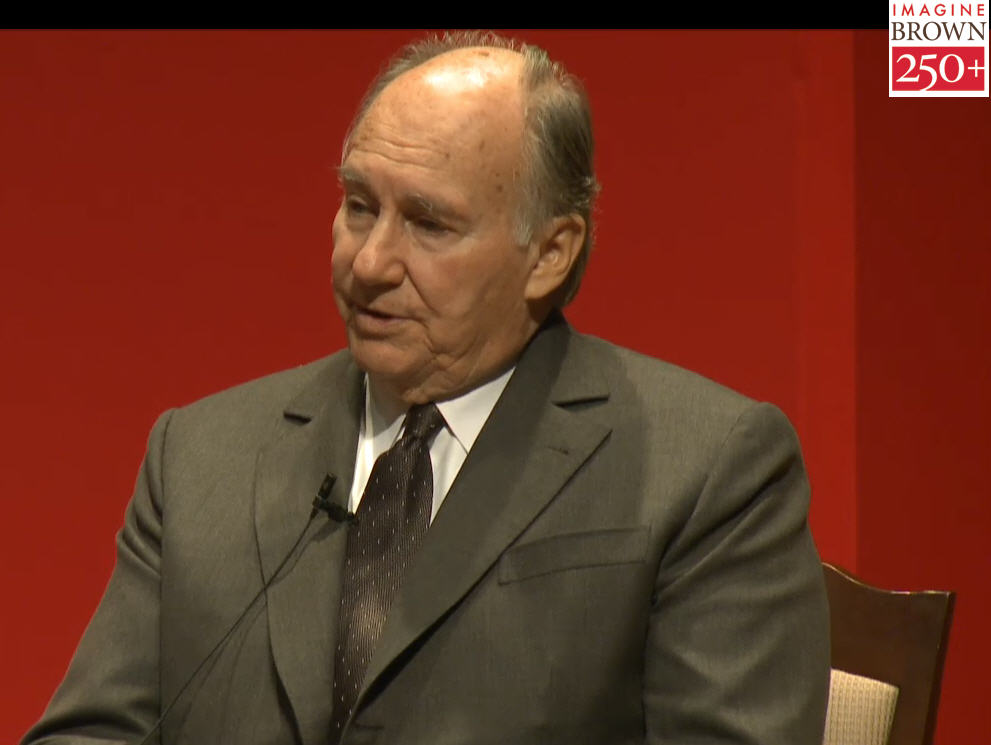

PROVIDENCE, R.I. – The Aga Khan, the 77-year-old spiritual leader for Shia Ismaili Muslims, is speaking at Brown University on Monday evening as part of the university’s 250th anniversary celebrations.

The Aga Khan will deliver Brown’s 88th Ogden Lecture on International Affairs starting at 5 p.m. It can be streamed live online.

The Aga Khan, whose given name is Prince Karim Al Hussein and who is known to Ismaili Muslims as “Mawlana Hazar Imam,” is believed to be a direct descendant of Mohammed, Islam’s most revered prophet.

A Harvard graduate and former university soccer player, he is the 49th imam, or spiritual leader for Shia Ismaili Muslims, a sect of Islam with some 15 million followers worldwide. He assumed the role in 1957, succeeding his grandfather.

The Aga Khan is also one of the world’s richest royals. According to Forbes, his fortune was pegged at about $800 million in 2009.

He was born in Geneva, Switzerland and currently lives in England, where he is a businessman with interests in thoroughbred horse racing and hotels.

He is also chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network, a nonprofit development organization he founded in 1981 to address hunger and disease and improve literacy, primarily in Africa and Asia.

Muslim leader the Aga Khan to speak at Brown Monday evening

March 10, 2014 04:21 PM

0 7 +10 0 0 0

By Philip Marcelo

pmarcelo@providencejournal.com

PROVIDENCE, R.I. – The Aga Khan, the 77-year-old spiritual leader for Shia Ismaili Muslims, is speaking at Brown University on Monday evening as part of the university’s 250th anniversary celebrations.

The Aga Khan will deliver Brown’s 88th Ogden Lecture on International Affairs starting at 5 p.m. It can be streamed live online.

The Aga Khan, whose given name is Prince Karim Al Hussein and who is known to Ismaili Muslims as “Mawlana Hazar Imam,” is believed to be a direct descendant of Mohammed, Islam’s most revered prophet.

A Harvard graduate and former university soccer player, he is the 49th imam, or spiritual leader for Shia Ismaili Muslims, a sect of Islam with some 15 million followers worldwide. He assumed the role in 1957, succeeding his grandfather.

The Aga Khan is also one of the world’s richest royals. According to Forbes, his fortune was pegged at about $800 million in 2009.

He was born in Geneva, Switzerland and currently lives in England, where he is a businessman with interests in thoroughbred horse racing and hotels.

He is also chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network, a nonprofit development organization he founded in 1981 to address hunger and disease and improve literacy, primarily in Africa and Asia.

From akdn.org

The 88th Stephen Ogden Lecture delivered by His Highness the Aga Khan at Brown University on 10 March 2014.

10 March 2014

Bismillah-ir-Rahman-ir-Rahim

President Paxson,

Ogden Family representatives,

Brown University Faculty, Students and Alumni,

Distinguished Guests,

Ladies and Gentlemen:

Thank you very much, Madame President, for your very kind introduction. It is a great honour for me to give the Ogden Lecture, to be included in the distinguished company of past Ogden Lecturers, and to pay tribute to the memory of Stephen Ogden.

I am also delighted to be present for the opening weekend of Brown’s 250th Anniversary, or one might say, the happy conclusion of Brown’s first quarter of a millennium!!

I have long felt a close sense of belonging at Brown; my eldest son was a member of the Brown Class of 1995, and I treasure the fact that I received an honorary degree from Brown, and was privileged at that time to give the Baccalaureate Address.

My own education has blended Islamic and Western traditions. I was studying at Harvard some 56 years ago when I inherited the Ismaili Imamat. It is not a political role, as has been mentioned, but let me emphasise that Islamic belief sees the spiritual and material worlds as inextricably connected. Faith should deepen our concern for improving the quality of human life in all of its dimensions. That is the overarching objective of the Aga Khan Development Network, which President Paxson has described so well.

It has been said that giving an effective university lecture requires the boldness to make some strong predictions about the future. I might suggest that President Paxson has put me in a slightly embarrassing position today, by inviting me to return to speak on the Brown campus. The challenge with coming back to give a second such lecture is that you have to explain what you got wrong the first time!

As I look back, over some 18 years now, to 1996, I think I actually under-estimated how many things would change in the years ahead. If you were a student at Brown 18 years ago, you would not have had any Facebook friends and you wouldn't be following anyone on Twitter. And, even more sadly perhaps, no one would be following you!

There was no instant messaging at that time; indeed, as I recall, people actually used their telephones primarily for talking!

In fact, email itself was still quite a new thing in 1996. And those are only the most obvious examples of transformative change in our world.

What has been the impact of such changes? We often think about technological innovation as a great source of hope for the world. We hear about how the internet can reach out across boundaries, helping us all to stay in touch, and giving us access to information from every imaginable source.

But it is worth remembering that the same affirmations have greeted new communication technologies for centuries, from the printing press to the telegraph to television and radio. Yet in each case, while many hopes were fulfilled, many were also disappointed. In the final analysis, the key to human cooperation and concord has not depended on advances in the technologies of communication, but rather on how human beings go about using – or abusing – their technological tools.

Among the risks of our new communications world is its potential contribution to what I would call the growing “centrifugal forces” in our time – the forces of “fragmentation.” These forces, I believe, can threaten the coherence of democratic societies and the effectiveness of democratic institutions.

Yes, the Information Revolution, for individuals and for communities, can be a great liberating influence. But it also carries some important risks.

More information at our fingertips can mean more knowledge and understanding. But it can also mean more fleeting attention-spans, more impulsive judgments, and more dependence on superficial snapshots of events. Communicating more often and more easily can bring people closer together, but it can also tempt us to live more of our lives inside smaller information bubbles, in more intense but often more isolated groupings.

We see more people everywhere these days, standing or sitting or walking alone, absorbed in their hand-held screens. But, I wonder whether, in some larger sense, they are really more “in touch?” Greater “connectivity” does not necessarily mean greater “connection.”

Information travels more quickly, in greater quantities these days. But the incalculable multiplication of information can also mean more error, more exaggeration, more misinformation, more disinformation, more propaganda. The world may be right there on our laptops, but the truth about the world may be further and further away.

The problem of fragmentation in our world is not a problem of diversity. Diversity itself should be a source of enrichment. The problem comes when diverse elements spin off on their own, when the bonds that connect us across our diversities begin to weaken.

Too often, as the world grows more complex, the temptation for some is to shield themselves from complexity, we seek the comfort of our own simplicities, our own specialities. As has often been said, we risk learning more and more, about less and less. And the result is that significant knowledge gaps can develop and persist.

The danger is that knowledge gaps so often run the risk of becoming empathy gaps. The struggle to remain empathetically open to the Other in a diversifying world is a continuing struggle of central importance for all of us.

The danger of having knowledge gaps grow into empathy gaps – that was the theme of my address in 1996. I discussed then what was becoming an enormous knowledge gap, nearly an ignorance gap, between the worlds of Islam and the non-Muslim world. Since that time, to be sure, there have been moments of encouraging progress on this front, including academic-centred efforts here at Brown, with your wonderful Digital Islamic Humanities Project.

But in many ways, that knowledge gap has worsened.

We have heard predictions for some years now about some inevitable clash of the industrial West with the Muslim world. These multiplied, of course, in the wake of the 9/11 tragedies and other violent episodes. But most Muslims don’t think that way; only an extreme minority does. For most of us, there is singularly little in our theology that would clash with the other Abrahamic faiths, with Christianity and Judaism. And there is much more in harmony. What has happened to the Islamic tradition that says that our best friends will be from the other Abrahamic Faiths, known as the “People of the Book”, all of whose faith builds on monotheistic revelation?

Of course, much of what the West has seen about the Muslim world in recent years has been through a media lens of instability and confrontation. What is highly abnormal in the Islamic world thus often gets mistaken for what is normal. But that is all the more reason for us to work from all directions to replace fearful ignorance with empathetic knowledge.

Down through many centuries, great Muslim cultures were built on the principle of inclusiveness. Some of the best minds and creative spirits from every corner of the world, independent of ethnic or religious identities, were brought together at great Muslim centres of learning. My own ancestors, the Fatimids, founded one of the world’s oldest universities, Al-Azhar in Cairo, over a thousand years ago. In fields of learning from mathematics to astronomy, from philosophy to medicine Muslim scholars sharpened the cutting edge of human knowledge. They were the equivalents of thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, Galileo and Newton. Yet their names are scarcely known in the West today. How many would recognise the name al-Khwarizmi – the Persian mathematician who developed some 1,200 years ago the algorithm, which is the foundation of search engine technology?

In the Muslim world itself, as is true outside of it, much of our history, culture and art, has been obscured, and with it a clear sense of Muslim diversity. Among other “in-comprehensions” is the increasing conflict between Sunni and Shia Muslims. In places like Pakistan and Malaysia, Iraq and Syria, Lebanon and Bahrain, Yemen and Somalia and Afghanistan, the Sunni-Shia conflict is becoming an absolute disaster.

The harsh truth is that religious hostility and intolerance, between as well as within religions, is contributing to violent crises and political impasse all across the world, in the Central African Republic, in South Sudan and Nigeria; in Myanmar, in the Philippines and in the Ukraine, and in many other places.

Such hostilities, of course, represent the most sinister side of what I have described as the centrifugal, fragmenting patterns of our times.

How can we respond to such tendencies? The response, I would emphasise today is a thoughtful, renewed commitment to the concept of pluralism and to the closely related potential of civil society.

A pluralist commitment is rooted in the essential unity of the human race. Does the Holy Quran not say that mankind is descended from “a single soul?” In an increasingly cosmopolitan world, it is essential that we live by a “cosmopolitan ethic,” one that addresses the age-old need to balance the particular and the universal, to honour both human rights and social duties, to advance personal freedom and to accept human responsibility.

It is in that spirit that we can nurture bonds of confidence across different peoples and unique individuals, welcoming the growing diversity of our world, even in matters of faith, as a gift of the Divine. Difference, in this context, can become an opportunity – not a threat – a blessing rather than a burden.

This brings us to the challenges for governance in our time. How do we organise our complex societies to achieve harmony and perhaps some progress, even at this time of growing diversity? These have always been difficult questions and they are not getting any easier. As you know, they were particularly difficult questions for the United States back in this university’s earliest years, as 13 former colonies tried to write a new national constitution.

George Washington, who had presided over the Constitutional Convention, came to this campus in 1790, after just one year as President, when Brown itself was only a quarter of a century old. He travelled to Providence to mark the recent adoption of the new US Constitution by the state of Rhode Island – the last of the original 13 states to do so. His visit was to celebrate the completion of that constitution-writing process. You may have known about this from reading the plaque that still hangs on the wall of University Hall, on the Brown Main Green, where Washington strolled that day with the university’s president.

I am told, incidentally, that Washington was greeted here with “the roar of cannons and the ringing of bells, and in a spirit of great Decorum.” I don’t know about the cannon and the bells, but I must testify, as a current university guest, that the “great decorum” has not changed at all! Thank you!

Washington’s visit in Providence marked a moment of historic constitutional significance. And the questions we have raised today, balancing centrifugal, fragmenting realities on the one hand with the imperatives of national bonding and governing on the other, were central concerns for Washington at that moment and throughout his career. After eight years of coping with these issues as the first American president, he made them the major theme of his famous Farewell Address.

He was worried, principally, he said then, about what he called the spirit of “faction” and its ability to undermine a sense of democratic nationhood. He described faction as a spirit, that “kindles the animosity of one part against another,” creating a “fatal tendency to elevate a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community” against the whole. It threatened, he said, “a frightful despotism”, one that could “render alien to each other those who ought to be bound together…”

Such threats to bonding, and thus to balance, have long presented a central governance challenge, here and elsewhere. And these issues are now being addressed with new intensity all across the world.

Amazing as it may seem, fully 37 countries have been writing or rewriting their constitutions in the last ten years, with another 12 countries recently embarking on this path. This means that nearly 25 per cent of the member countries of the United Nations have been rethinking these central governance concerns. And nearly half of these 49 countries have majority Muslim populations.

Clearly, many Muslim societies are seeking new ways to organise themselves. And there can be no “one size fits all”. The outcomes obviously are going to be many and varied. The process will challenge the creativity of the world’s best political and legal thinkers. Especially in the developing world, such matters will increasingly be in the hands of younger, more educated men and women, provided the system allows them to come to the forefront.

These governance issues are frankly today, of global concern. And I believe that the great universities of the world and Brown University in particular, can also play an especially creative role in responding to them.

The challenge, as we have said, will be one of balancing values and interests, honouring the importance of religious and ethical traditions, for example, while also respecting the free will of individual human beings; accommodating both the role of central governments and regional demands, reconciling the urban and the rural; providing for democratic change, and institutional continuity.

Creating new governance frameworks is obviously not an easy task. But it can be accomplished. In Kenya just three and a half years ago, for example, a new constitution ratified by two- thirds of the voters, redistributed power dramatically from the central level to 47 county governments. In Tunisia, just a few weeks ago, a new “consensus” constitution with 94 per cent approval from the elected Constituent Assembly reaffirmed the Islamic identity of the Tunisian state, while also protecting the human rights of religious and ethnic minorities.

In these cases, and in other places such as Bangladesh, one of the fundamental constructive forces at work has been the strength of civil society, it is a topic that is worth serious attention. And, I am happy to say, that it has been getting increasing attention, including the exemplary, cutting-edge work here at Brown of the Watson Institute for International Studies.

By civil society I mean an array of institutions that operate on a private, voluntary basis, but are motivated by high public purposes. They include institutions devoted to culture, to science and to research; to commercial, labour, ethnic and religious concerns; as well as a variety of professional societies. They include institutions of the media and education.

I think the conclusion is the success of democratic societies will depend in the end on more than democratic governments. The scale and the quality of civil society will become a factor, I believe, of enormous importance.

A quality civil society has three critical underpinnings: a commitment to pluralism, an open door to meritocracy, and a full embrace of what I described earlier as a cosmopolitan ethic.

The voices of civil society will reflect and express the growing complexity of society, not as autonomous fragments, but as diversified institutions seeking the common good. And I believe that the voices of civil society can be among the most powerful forces in our time. Where change has been overdue, they can be voices for change. Where people live in fear, they can be voices of hope.

One of the energising forces that makes a quality civil society possible, of course, is the readiness of its citizens to contribute their talents and energies to the social good. What is required is a profound spirit of voluntary service, a principle cherished in Shia Ismaili culture, and honoured, I know, here at Brown.

Progress is possible when the multiple, diversified needs of any society can be matched by multiple, diversified inputs; that is also what civil society is all about. This is why great universities, with their broad, diversified programmes, can be a resource of importance in the development of quality civil society, in their own countries but also around the world. And again, Brown offers a powerful example.

Perhaps the biggest quandary we face in our economic and social development programmes is the problem of “predictability”; knowing what changes are going to arise, and then deciding what is more or less likely to work in a given situation. But again, progress is possible when complex issues are subjected to competent, intelligent, nuanced and sophisticated analysis, free from dogmatism, and based upon what I would describe as “empathetic knowledge.” This happens best in open, meritocratic societies, where people’s responsibilities are based on their competence. It also happens best when the intellectual resources of the world’s great universities, like Brown, are brought into play.

One of the important values of the Shia Ismaili tradition is the transformative power of the human intellect – that conviction underscores AKDN’s strong commitment to education, at all levels, wherever we are present. These activities include the Aga Khan University – now thirty years old – our newer University of Central Asia, our Aga Khan Academies at the primary and secondary levels, and our major commitment to the potential of Early Childhood Development.

The Aga Khan University in Karachi and East Africa is in the process today of creating a new Liberal Arts faculty, while also establishing eight new post-graduate schools. I would emphasise both these initiatives. Professional education is sorely needed in the developing world, but equally important is the capacity to integrate knowledge, to nurture critical thinking and ethical sensitivity and to advance interdisciplinary teaching and research.

A quality civil society, in any setting, will require well-informed leaders who are sensitive to a wide array of disciplines, and outlooks and cultures. It will require people with the ability to continue their learning in response to new knowledge. I know these are central concerns for Brown University, articulated so well in its new Strategic Plan and its call for “Building on Distinction.”

As we look ahead, in sum, we face a world in which centrifugal and fragmenting influences are of growing importance, presenting new governance challenges all across the planet, and especially in fragile societies. In such a world, the voices of pluralistic civil society can help ensure that diversity does not lead to disintegration, and that a broad variety of energies and talents can be enlisted in the quest for human progress. Diversification without disintegration, this is the greatest challenge of our time.

Over the past six decades I have been immersed in the problems of developing societies, grappling with ways to assist their populations, despite both natural hazards and human errors. It is my conviction that a strong, high-quality, ethical and competent civil society is one of the greatest forces we can work with to underwrite such progress. And, if this is correct, then the role of great universities has never been more important.

I am convinced that Brown will be among the greatest universities stepping up to this challenge, as it finishes its first 250 years, and embarks on its next quarter of a millennium!

Thank you.

Video of the event on YouTube and other sites

www.youtube.com/embed/vSvXca3OiZo

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tz4qYoIcMlY

http://link.brightcove.com/services/pla ... 7210350001

www.youtube.com/embed/vSvXca3OiZo

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tz4qYoIcMlY

http://link.brightcove.com/services/pla ... 7210350001

Last edited by Admin on Wed Mar 12, 2014 8:27 pm, edited 1 time in total.

The mention about Copyright is 13:25 min into the video onAdmin wrote:The above is not an accurate transcript of the speech. The part on Copyright, and lawyers making money out of it is missing. What else is missing?

http://www.youtube.com/embed/vSvXca3OiZo

And you can see Prince Rahim laughing... he knows why Imam is mentioning this.

providencejournal.com/breaking-news/content/20140310-aga-khan-speaking-at-brown-sees-virtue-in-social-media-internet-technology.ece

By PHILIP MARCELO

JOURNAL STATE HOUSE BUREAU

pmarcelo@providencejournal.com

PROVIDENCE — Speaking at Brown University on Monday, the Aga Khan — the spiritual leader for some 15 million Shia Ismaili Muslims worldwide — focused on the potential of social media and Internet-based technology to bridge cultural divisions.

But the 77-year-old Harvard graduate, whose appearance was part of the university’s 250th anniversary celebration this month, also warned of how that technology can shield people from how complex the world really is.

“More information at our fingertips can mean more knowledge and understanding, but it can also mean more fleeting attention spans, more impulsive judgments and more superficial snapshots of events,” said the Aga Khan, whose given name is Prince Karim Al Husseini. “Our world grows more complex, but too often the temptation is to shield [ourselves] from complexity.”

Addressing what some have referred to as the “inevitable clash” between the Muslim world and the industrialized West, the Aga Khan, who is believed to be a direct descendant of the prophet Mohammed, argued that there is “much more in harmony” between the two cultures.

Centuries ago, he said, Islamic culture flourished because of its “inclusiveness,” with “great Muslim centers of learning” bringing together people from different cultures to enrich mankind’s understanding of the world.

“What the West has seen of the Muslim world has been through a media lens of instability and confrontation. What is highly abnormal in the Islamic world often gets mistaken for what is normal,” the Aga Khan said. “That is all the more reason for us to work from all directions to replace fearful ignorance with empathetic knowledge.”

On the continued tensions between Sunni and Shia Muslims — Islam’s two major sects — he called for a “thoughtful, renewed emphasis” on “pluralism” and “civil society.”

“Does the Holy Koran not say that mankind is descended from a single soul?” said the Aga Khan, who is the 49th imam, or spiritual leader for Ismaili Muslims, a branch of Shia Islam. “In an increasingly cosmopolitan world, it is essential that we live by a cosmopolitan ethic, one that honors human rights and social duties [and] advances personal freedom.”

Born in Switzerland and currently living in Europe, the Aga Khan is also chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network, a nonprofit development organization he founded in 1981.

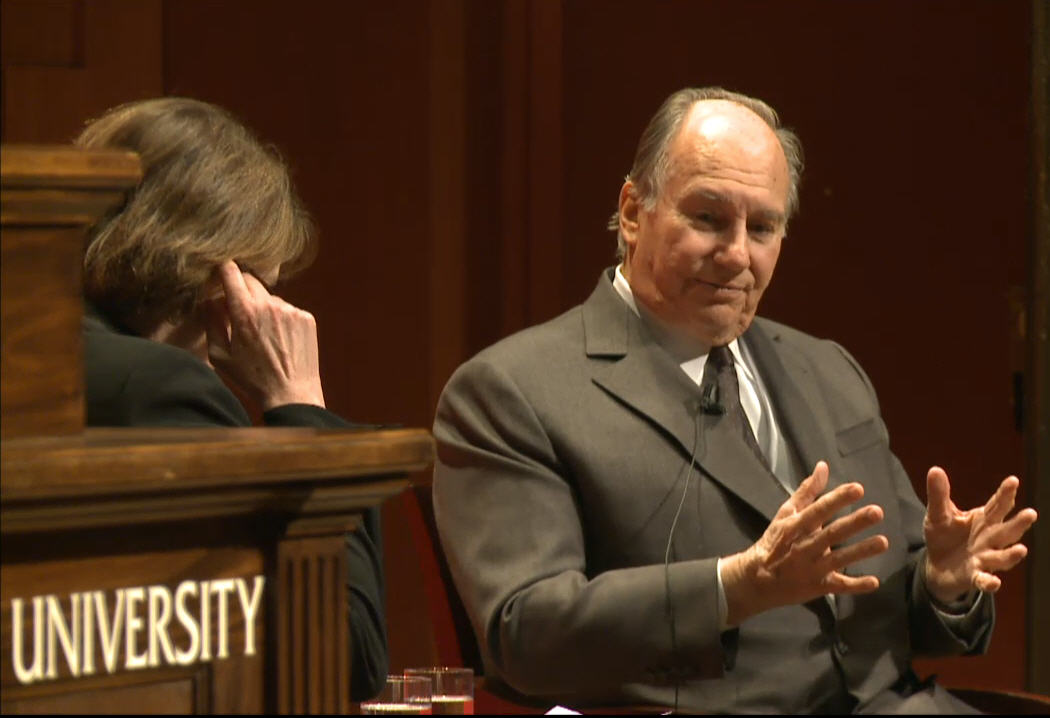

In his prepared remarks and a question-and-answer session with Brown University President Christina Paxson, he highlighted that organization’s work in the areas of health care and education in Africa and Asia.

The Aga Khan said universities and non-governmental institutions like his must continue to be agents for change in the developing world.

“The success of democracy will require more than democratic governments,” he said. “In places where people live in fear, they can be voices of hope.”

The message resonated with a number of those in attendance Monday.

“There was just so much in there about Brown and the role these top Western universities should play in development,” said Aarish Rojiani, a high school senior from Georgia who attended with his family and was among many Shia Ismaili Muslims in the packed auditorium. “It was a great point to make at a place like this.”

Tahira Dosani, a Brown graduate who lives in Washington, D.C., said she was impressed by the Aga Khan’s remarks about technology: “He said global connectivity doesn’t necessarily mean more connection. I think that was powerful.”

By PHILIP MARCELO

JOURNAL STATE HOUSE BUREAU

pmarcelo@providencejournal.com

PROVIDENCE — Speaking at Brown University on Monday, the Aga Khan — the spiritual leader for some 15 million Shia Ismaili Muslims worldwide — focused on the potential of social media and Internet-based technology to bridge cultural divisions.

But the 77-year-old Harvard graduate, whose appearance was part of the university’s 250th anniversary celebration this month, also warned of how that technology can shield people from how complex the world really is.

“More information at our fingertips can mean more knowledge and understanding, but it can also mean more fleeting attention spans, more impulsive judgments and more superficial snapshots of events,” said the Aga Khan, whose given name is Prince Karim Al Husseini. “Our world grows more complex, but too often the temptation is to shield [ourselves] from complexity.”

Addressing what some have referred to as the “inevitable clash” between the Muslim world and the industrialized West, the Aga Khan, who is believed to be a direct descendant of the prophet Mohammed, argued that there is “much more in harmony” between the two cultures.

Centuries ago, he said, Islamic culture flourished because of its “inclusiveness,” with “great Muslim centers of learning” bringing together people from different cultures to enrich mankind’s understanding of the world.

“What the West has seen of the Muslim world has been through a media lens of instability and confrontation. What is highly abnormal in the Islamic world often gets mistaken for what is normal,” the Aga Khan said. “That is all the more reason for us to work from all directions to replace fearful ignorance with empathetic knowledge.”

On the continued tensions between Sunni and Shia Muslims — Islam’s two major sects — he called for a “thoughtful, renewed emphasis” on “pluralism” and “civil society.”

“Does the Holy Koran not say that mankind is descended from a single soul?” said the Aga Khan, who is the 49th imam, or spiritual leader for Ismaili Muslims, a branch of Shia Islam. “In an increasingly cosmopolitan world, it is essential that we live by a cosmopolitan ethic, one that honors human rights and social duties [and] advances personal freedom.”

Born in Switzerland and currently living in Europe, the Aga Khan is also chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network, a nonprofit development organization he founded in 1981.

In his prepared remarks and a question-and-answer session with Brown University President Christina Paxson, he highlighted that organization’s work in the areas of health care and education in Africa and Asia.

The Aga Khan said universities and non-governmental institutions like his must continue to be agents for change in the developing world.

“The success of democracy will require more than democratic governments,” he said. “In places where people live in fear, they can be voices of hope.”

The message resonated with a number of those in attendance Monday.

“There was just so much in there about Brown and the role these top Western universities should play in development,” said Aarish Rojiani, a high school senior from Georgia who attended with his family and was among many Shia Ismaili Muslims in the packed auditorium. “It was a great point to make at a place like this.”

Tahira Dosani, a Brown graduate who lives in Washington, D.C., said she was impressed by the Aga Khan’s remarks about technology: “He said global connectivity doesn’t necessarily mean more connection. I think that was powerful.”

AS RECEIVED:

This was said by H.H. The Aga Khan in his Ogden Speech but is missing in the transcript above taken from akdn.org

March 10, Brown University lecture deleted written version (between 13:00 – 14:30 minutes into the speech)

“I wonder what would have had happened if Al-Khwarizmi had patented or copyrighted his algorithm, and I try to analyze what would be the consequences.

Well, the first consequence is the copyright lawyers around the world would either be billionaires or burst. Those who have broken the copyright would be billionaires and others would be good bye.

Secondly the programs probably itself would have been renamed, so if they had been renamed either they would have Muslims name or they would keep their names. If they have Muslim names they would in Arabic or Turkish or Persian or Urdu and none of you would be able to pronounce those names. If the names were kept then they would be printed in the developing world and you know what’s it’s like to print English in the developing world, so the twitter would become twit, Google would became giggle and a good friend Bill Gates would be “demonstrated a gesture of something disappearing … poof” that would be the end of Bill Gates.

But I can’t be serious all the time and sometime I like a good laugh. So I on the other hand must get back to serious matters because this is suppose to be a serious lecture.”

This was said by H.H. The Aga Khan in his Ogden Speech but is missing in the transcript above taken from akdn.org

March 10, Brown University lecture deleted written version (between 13:00 – 14:30 minutes into the speech)

“I wonder what would have had happened if Al-Khwarizmi had patented or copyrighted his algorithm, and I try to analyze what would be the consequences.

Well, the first consequence is the copyright lawyers around the world would either be billionaires or burst. Those who have broken the copyright would be billionaires and others would be good bye.

Secondly the programs probably itself would have been renamed, so if they had been renamed either they would have Muslims name or they would keep their names. If they have Muslim names they would in Arabic or Turkish or Persian or Urdu and none of you would be able to pronounce those names. If the names were kept then they would be printed in the developing world and you know what’s it’s like to print English in the developing world, so the twitter would become twit, Google would became giggle and a good friend Bill Gates would be “demonstrated a gesture of something disappearing … poof” that would be the end of Bill Gates.

But I can’t be serious all the time and sometime I like a good laugh. So I on the other hand must get back to serious matters because this is suppose to be a serious lecture.”

AS RECEIVED:

This was said by H.H. The Aga Khan in his Ogden Speech but is missing in the transcript above taken from akdn.org

March 10, Brown University lecture deleted written version (between 13:00 – 14:30 minutes into the speech)

“I wonder what would have had happened if Al-Khwarizmi had patented or copyrighted his algorithm, and I try to analyze what would be the consequences.

Well, the first consequence is the copyright lawyers around the world would either be billionaires or burst. Those who have broken the copyright would be billionaires and others would be good bye.

Secondly the programs probably itself would have been renamed, so if they had been renamed either they would have Muslims name or they would keep their names. If they have Muslim names they would in Arabic or Turkish or Persian or Urdu and none of you would be able to pronounce those names. If the names were kept then they would be printed in the developing world and you know what’s it’s like to print English in the developing world, so the twitter would become twit, Google would became giggle and a good friend Bill Gates would be “demonstrated a gesture of something disappearing … poof” that would be the end of Bill Gates.

But I can’t be serious all the time and sometime I like a good laugh. So I on the other hand must get back to serious matters because this is suppose to be a serious lecture.”

This was said by H.H. The Aga Khan in his Ogden Speech but is missing in the transcript above taken from akdn.org

March 10, Brown University lecture deleted written version (between 13:00 – 14:30 minutes into the speech)

“I wonder what would have had happened if Al-Khwarizmi had patented or copyrighted his algorithm, and I try to analyze what would be the consequences.

Well, the first consequence is the copyright lawyers around the world would either be billionaires or burst. Those who have broken the copyright would be billionaires and others would be good bye.

Secondly the programs probably itself would have been renamed, so if they had been renamed either they would have Muslims name or they would keep their names. If they have Muslim names they would in Arabic or Turkish or Persian or Urdu and none of you would be able to pronounce those names. If the names were kept then they would be printed in the developing world and you know what’s it’s like to print English in the developing world, so the twitter would become twit, Google would became giggle and a good friend Bill Gates would be “demonstrated a gesture of something disappearing … poof” that would be the end of Bill Gates.

But I can’t be serious all the time and sometime I like a good laugh. So I on the other hand must get back to serious matters because this is suppose to be a serious lecture.”

browndailyherald.com/2014/03/11/aga-khan-stresses-importance-pluralism/

University News

Aga Khan stresses importance of pluralism

Aga Khan emphasizes collective responsibility, cracks jokes in talk on tradition and technology

By Caroline Kelly

Senior Staff Writer

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

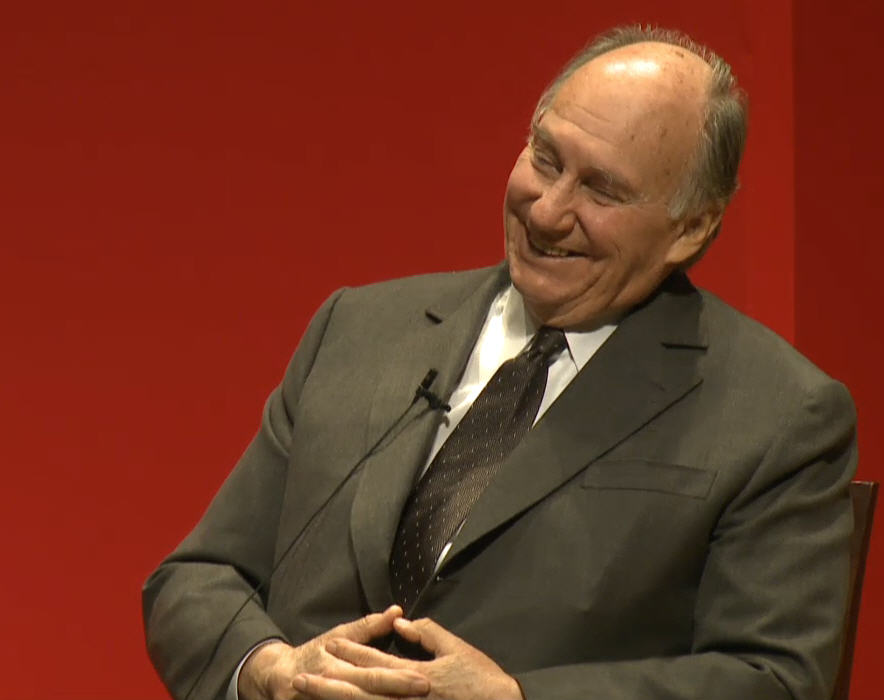

There was room for both social media jokes and a thoughtful discussion of modern communication in Prince Karim Aga Khan IV’s lecture yesterday.

Prince Karim Aga Khan IV ’96 hon. P’95 said during a lecture Monday that the hardest part of speaking at Brown again since delivering the baccalaureate address in 1996 was “that you have to explain what you got wrong the first time.” It was hard to imagine that the thorough, well-spoken 49th hereditary imam of Nizari Ismailism would be prone to carelessness.

But he insisted. “I think I actually underestimated what happened in the 18 years ahead,” he said, acknowledging that back then, “you would not have had any Facebook friends, and you would not be following anyone on Twitter, and perhaps more sadly, no one would be following you,” to much laughter from the audience.

Introduced by President Christina Paxson, the Aga Khan’s speech was a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs and focused on the importance of a relevant education.

The Aga Khan is the founder and chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network, whose agencies include the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development, founded in 1967 to fight rural poverty and hunger in disenfranchised nations, and the Aga Khan Education Services. The latter include the Aga Khan Academies, residential private schools in Africa and Asia following the International Baccalaureate curriculum, and the Aga Khan Universities, which place an emphasis on pluralism and collective responsibility, according to the event brochure.

The Aga Khan described how his “own education has blended both Islamic and western traditions.” He said his position is “not a political role, as has been mentioned, but let me emphasize that Islamic belief sees the spiritual and material worlds as inextricably connected. Faith should deepen our concern for improving the quality of human life in all its dimensions.”

After his lighthearted foray into social media humor, the Aga Khan adopted a more serious tone. “We often think about technological innovation as a great source of hope for the world, (and) we hear about how the Internet can reach out across boundaries, helping us all to stay in touch,” he said.

But the success of our use of modern communication depends on “how human beings go about using or abusing their technological tools,” the Aga Khan said, fearing “centrifugal forces in our time, the forces of fragmentation” that can “threaten democratic institutions.” He described how technological access to constant information can lead to “more fleeting attention spans, more impulsive judgments and more dependence on superficial snapshots of events.”

In light of the temptation to “live more of our lives inside smaller information bubbles, in more intense and often more isolated groupings,” the Aga Khan stressed that “greater connectivity does not necessarily mean greater connection.” With more room for error, the enriching nature of diversity is lost, he said, noting that “the problem comes when diverse elements spin off on their own, when the bonds that connect us across our diversities begin to weaken.”

He cited the West’s perception of the Islamic world as an area where it is important to “replace fearful ignorance with empathetic knowledge,” describing how “knowledge gaps so often run the risk of becoming empathy gaps,” the topic of his first speech at Brown, which he still sees as pertinent. “The struggle to remain empathetic and open to the other in a diversifying world is a continuing struggle of central importance to all of us,” he said.

To solve these problems, the Aga Khan called for a “thoughtful, renewed commitment to the concept of pluralism” to foster the “essential unity of the human race.” He described the importance of “the capacity to integrate knowledge, to nurture critical thinking and ethical sensitivity” in preparing “well-informed leaders who are sensitive to a wide array of disciplines and conflicts and cultures.”

After his speech, the Aga Khan participated in a question-and-answer session with Paxson, who drew from a list of questions contributed by members of the Brown community.

In response to a question about the Aga Khan’s work “to improve public health,” he said his organization has noted a significant change in disease spread in the developing world. “If you speak to most of the governments in the developing world, they are particularly unhappy about the cost of non-communicable diseases,” he said.

This dissatisfaction means focusing on “hospital beds, tertiary care” and an effort to “use technology to link rural, isolated areas to (their) own networks,” he said.

When Paxson asked what advice he had for students “looking forward to making a difference in the world,” he noted the importance of being able to access the world, saying, “If you speak seven languages, your horizons are widened.

“If you want to be a global citizen, then prepare yourself for that — it’s a different set of goals,” he added.

Lastly, the Aga Khan acknowledged the importance of persevering despite mistakes. “Everybody makes mistakes — never regret them, but correct them,” he said. “There’s no such thing as a perfect world or a perfect life.”

University News

Aga Khan stresses importance of pluralism

Aga Khan emphasizes collective responsibility, cracks jokes in talk on tradition and technology

By Caroline Kelly

Senior Staff Writer

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

There was room for both social media jokes and a thoughtful discussion of modern communication in Prince Karim Aga Khan IV’s lecture yesterday.

Prince Karim Aga Khan IV ’96 hon. P’95 said during a lecture Monday that the hardest part of speaking at Brown again since delivering the baccalaureate address in 1996 was “that you have to explain what you got wrong the first time.” It was hard to imagine that the thorough, well-spoken 49th hereditary imam of Nizari Ismailism would be prone to carelessness.

But he insisted. “I think I actually underestimated what happened in the 18 years ahead,” he said, acknowledging that back then, “you would not have had any Facebook friends, and you would not be following anyone on Twitter, and perhaps more sadly, no one would be following you,” to much laughter from the audience.

Introduced by President Christina Paxson, the Aga Khan’s speech was a Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs and focused on the importance of a relevant education.

The Aga Khan is the founder and chairman of the Aga Khan Development Network, whose agencies include the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development, founded in 1967 to fight rural poverty and hunger in disenfranchised nations, and the Aga Khan Education Services. The latter include the Aga Khan Academies, residential private schools in Africa and Asia following the International Baccalaureate curriculum, and the Aga Khan Universities, which place an emphasis on pluralism and collective responsibility, according to the event brochure.

The Aga Khan described how his “own education has blended both Islamic and western traditions.” He said his position is “not a political role, as has been mentioned, but let me emphasize that Islamic belief sees the spiritual and material worlds as inextricably connected. Faith should deepen our concern for improving the quality of human life in all its dimensions.”

After his lighthearted foray into social media humor, the Aga Khan adopted a more serious tone. “We often think about technological innovation as a great source of hope for the world, (and) we hear about how the Internet can reach out across boundaries, helping us all to stay in touch,” he said.

But the success of our use of modern communication depends on “how human beings go about using or abusing their technological tools,” the Aga Khan said, fearing “centrifugal forces in our time, the forces of fragmentation” that can “threaten democratic institutions.” He described how technological access to constant information can lead to “more fleeting attention spans, more impulsive judgments and more dependence on superficial snapshots of events.”

In light of the temptation to “live more of our lives inside smaller information bubbles, in more intense and often more isolated groupings,” the Aga Khan stressed that “greater connectivity does not necessarily mean greater connection.” With more room for error, the enriching nature of diversity is lost, he said, noting that “the problem comes when diverse elements spin off on their own, when the bonds that connect us across our diversities begin to weaken.”

He cited the West’s perception of the Islamic world as an area where it is important to “replace fearful ignorance with empathetic knowledge,” describing how “knowledge gaps so often run the risk of becoming empathy gaps,” the topic of his first speech at Brown, which he still sees as pertinent. “The struggle to remain empathetic and open to the other in a diversifying world is a continuing struggle of central importance to all of us,” he said.

To solve these problems, the Aga Khan called for a “thoughtful, renewed commitment to the concept of pluralism” to foster the “essential unity of the human race.” He described the importance of “the capacity to integrate knowledge, to nurture critical thinking and ethical sensitivity” in preparing “well-informed leaders who are sensitive to a wide array of disciplines and conflicts and cultures.”

After his speech, the Aga Khan participated in a question-and-answer session with Paxson, who drew from a list of questions contributed by members of the Brown community.

In response to a question about the Aga Khan’s work “to improve public health,” he said his organization has noted a significant change in disease spread in the developing world. “If you speak to most of the governments in the developing world, they are particularly unhappy about the cost of non-communicable diseases,” he said.

This dissatisfaction means focusing on “hospital beds, tertiary care” and an effort to “use technology to link rural, isolated areas to (their) own networks,” he said.

When Paxson asked what advice he had for students “looking forward to making a difference in the world,” he noted the importance of being able to access the world, saying, “If you speak seven languages, your horizons are widened.

“If you want to be a global citizen, then prepare yourself for that — it’s a different set of goals,” he added.

Lastly, the Aga Khan acknowledged the importance of persevering despite mistakes. “Everybody makes mistakes — never regret them, but correct them,” he said. “There’s no such thing as a perfect world or a perfect life.”

americanbazaaronline.com/2014/03/12/aga-khan-gives-speech-brown-university-250th-anniversary-event/

Aga Khan stresses pluralism, dangers of too much technology in address at Brown University

March 12, 2014

Lecture given during celebration of school’s 250th anniversar.

By Deepak Chitnis

WASHINGTON, DC: Aga Khan, the leading religious figure for the roughly 15 million Shia Ismaili Muslims around the world, gave a lecture at Brown University on Monday, urging caution with regards to new and social media, and warning that an increased reliance on technology could lead to an inability to communicate face-to-face.

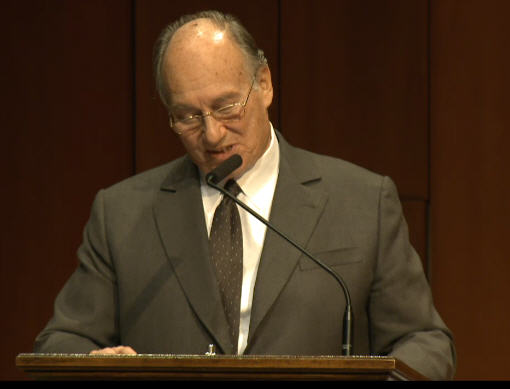

The Aga Khan (courtesy of Brown University)

Aga Khan (courtesy of Brown University)

Aga Khan did not criticize all technology, saying that when used properly, it can serve incredibly beneficial purposes. Specifically Aga Khan talked about how technology had recently been used assist in creating new governance frameworks in Kenya, Tunisia and Bangladesh.

“More information at our fingertips can mean more knowledge and understanding,” said Aga Khan. “But it can also mean more fleeting attention-spans, more impulsive judgments, and more dependence on superficial snapshots of events.”

During his speech, Aga Khan also talked about what he believes to be the critical underpinnings of society. “A quality civil society has three critical underpinnings: a commitment to pluralism, an open door to meritocracy, and a full embrace of […] a cosmopolitan ethic,” said Aga Khan, defining the latter term as “one that addresses the age-old need to balance the particular and the universal, to honor both human rights and social duties, to advance personal freedom and to accept human responsibility.”

In bringing up these points, Aga Khan returned to technology, saying how it was important to use it to spread knowledge, disseminate information, and facilitate communication, arguing that it was a lack of these elements that has fueled violent conflict in several regions around the world.

The harsh truth is that religious hostility and intolerance, between as well as within religions, is contributing to violent crises and political impasse all across the world, in the Central African Republic, in South Sudan and Nigeria; in Myanmar, in the Philippines and in the Ukraine, and in many other places,” said Aga Khan.

His remarks were given during the 88th Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs, which was part of Brown University celebrating its 250th anniversary. Aga Khan received an honorary doctorate from the University in 1996, and his son, Prince Rahim Aga Khan, graduated from the University the year before. In introducing Aga Khan, Brown University president Christina Paxson lauded him as a “returning friend” whose tireless work around the world was a model that all students and alumni of the University should follow.

Aga Khan is the 49th hereditary Imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslims, and is the founder and chairman of Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). In giving a speech at the Ogden Lectureship, which was established in 1965, he joins the likes of former speakers such as Mikhail Gorbachev, The Dalai Lama, and King Hussein of Jordan.

Aga Khan stresses pluralism, dangers of too much technology in address at Brown University

March 12, 2014

Lecture given during celebration of school’s 250th anniversar.

By Deepak Chitnis

WASHINGTON, DC: Aga Khan, the leading religious figure for the roughly 15 million Shia Ismaili Muslims around the world, gave a lecture at Brown University on Monday, urging caution with regards to new and social media, and warning that an increased reliance on technology could lead to an inability to communicate face-to-face.

The Aga Khan (courtesy of Brown University)

Aga Khan (courtesy of Brown University)

Aga Khan did not criticize all technology, saying that when used properly, it can serve incredibly beneficial purposes. Specifically Aga Khan talked about how technology had recently been used assist in creating new governance frameworks in Kenya, Tunisia and Bangladesh.

“More information at our fingertips can mean more knowledge and understanding,” said Aga Khan. “But it can also mean more fleeting attention-spans, more impulsive judgments, and more dependence on superficial snapshots of events.”

During his speech, Aga Khan also talked about what he believes to be the critical underpinnings of society. “A quality civil society has three critical underpinnings: a commitment to pluralism, an open door to meritocracy, and a full embrace of […] a cosmopolitan ethic,” said Aga Khan, defining the latter term as “one that addresses the age-old need to balance the particular and the universal, to honor both human rights and social duties, to advance personal freedom and to accept human responsibility.”

In bringing up these points, Aga Khan returned to technology, saying how it was important to use it to spread knowledge, disseminate information, and facilitate communication, arguing that it was a lack of these elements that has fueled violent conflict in several regions around the world.

The harsh truth is that religious hostility and intolerance, between as well as within religions, is contributing to violent crises and political impasse all across the world, in the Central African Republic, in South Sudan and Nigeria; in Myanmar, in the Philippines and in the Ukraine, and in many other places,” said Aga Khan.

His remarks were given during the 88th Stephen A. Ogden Jr. ’60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs, which was part of Brown University celebrating its 250th anniversary. Aga Khan received an honorary doctorate from the University in 1996, and his son, Prince Rahim Aga Khan, graduated from the University the year before. In introducing Aga Khan, Brown University president Christina Paxson lauded him as a “returning friend” whose tireless work around the world was a model that all students and alumni of the University should follow.

Aga Khan is the 49th hereditary Imam of the Shia Ismaili Muslims, and is the founder and chairman of Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN). In giving a speech at the Ogden Lectureship, which was established in 1965, he joins the likes of former speakers such as Mikhail Gorbachev, The Dalai Lama, and King Hussein of Jordan.

huffingtonpost.com/samreen-hooda/the-aga-khan-helps-brown-_b_4945075.html

March 13, 2014

The Aga Khan Helps Brown University Celebrate Its 250th

Posted: 03/12/2014 10:03 pm EDT Updated: 03/12/2014 11:59 pm EDT

By Shamez Babvani and Samreen Hooda

"George Washington...came to this campus in 1790, after just one year as President, when Brown itself was only a quarter of a century old,," His Highness the Aga Khan said on Monday during his own visit to Brown University's 250th anniversary celebration.

President Christina Paxson invited the Aga Khan to deliver the 88th Stephen A. Ogden, Jr. '60 Memorial Lecture on International Affairs, just a few weeks after his historic speech to both houses of the Canadian Parliament, the first Muslim non-head of state to address the Canadian Parliament, a country of which he is also an honorary citizen.

The Aga Khan, 49th hereditary Imam of some 15 million Shia Ismaili Muslims worldwide, explained in his address at the Canadian Parliament, that the Ismaili Imamat is a "supra-national entity, representing the succession of Imams since the time of the Prophet," and the Ismailis are the only Shia community who "throughout history, have been led by a living, hereditary Imam in direct descent from the Prophet."

Introducing his life's work as "critically important," President Paxson added that the Aga Khan's agencies span over 30 countries with 400 healthcare facilities, over 200 schools and an "annual budget for nonprofit development activities that is approximately $600 million," with "project companies associated with those efforts generating close to $3 billion in total revenue."

This would seem an unimaginable feat for a personality that is not the head of any state, nor governs any land. He describes his mandate for economic and educational development as part and parcel of his mantle and responsibility as Imam. Yet, the Aga Khan is constantly awarded head of state status, has agreements with national and state level governments including a number of African and Asian governments, Canada, Portugal as well as California, Illinois, and Texas, has established 6 Ismaili centers which serve as ambassadorial delegation buildings around the world, and has numerous honorary degrees and memorandums of understanding from prestigious universities including McGill, McMaster, Cambridge, Harvard and Brown, amongst others, along with many other awards and honors conferred upon him by leaders and dignitaries around the world. He is clearly a respected and admired figure who leaders and institutions around the world seek to partner with and listen to.

“To see a Muslim leader with such vision and compassion and engagement in a very positive way in society, yes I think it changes the public sense of what an Imam is, but I also think much more importantly it dignifies the office and the intention of the office,” said Reverend Janet Cooper Nelson, Chaplain of the University and Director of the Office of the Chaplains and Religious Life. “As a leader, I take quite a bit of model as well as encouragement from the care with which the Aga Khan presents himself. He does not take your good will or mine for granted. He tries to earn it.”

In his lecture at Brown, the Aga Khan spoke about technology, knowledge gaps and the challenges of modern government in our fast-paced world.

"Washington's visit in Providence marked a moment of historic constitutional significance... He was worried, principally, he said then, about what he called the spirit of "faction" and its ability to undermine a sense of democratic nationhood," the Aga Khan added, likening Washington's thoughts to the condition of our world today, in which nearly 25 percent of the member countries in the United Nations are writing or rewriting their constitutions. And 50 percent of those countries have majority Muslim populations.

"Clearly, many Muslim societies are seeking new ways to organise themselves. And there can be no 'one size fits all,' the Aga Khan said, adding that today's governance issues are of global relevance where great universities, particularly Brown, can play a pivotal role.

Unfortunately today, much of what is shown about Islam is a result of, as the Aga Khan puts it, "more fleeting attention-spans, more impulsive judgements, and more dependence on superficial snapshots of events," than it is on what Islam actually teaches and little to none is known about the history of Islam, beliefs and accomplishment of a majority of Muslims.

"My own ancestors, the Fatimids, founded one of the world's oldest universities, Al-Azhar in Cairo, over a thousand years ago," His Higness said "In fields of learning from mathematics to astronomy, from philosophy to medicine, Muslim scholars sharpened the cutting edge of human knowledge. They were the equivalents of thinkers like Plato and Aristotle, Galileo and Newton. Yet their names are scarcely known in the West today. How many would recognise the name al-Khwarizmi - the Persian mathematician who developed some 1,200 years ago the algorithm, which is the foundation of search engine technology?"