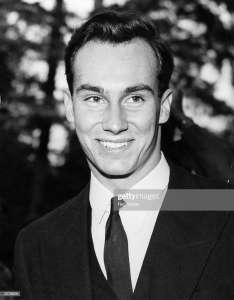

Interview of a Young Imam - 1958-05-02

=========

Mowlana Hazar Imam and the London Newspapermen on television.

May 2nd, 1958 "Press Conference"

115 Questions answered with artistry and insight.

Representatives of four leading English Newspapers viz, Marshall Pugh of the "Daily Mail", Rene McColl of the "Daily Express", John Connell of the Evening News and John Freeman, Assistant Editor of the "New Statesman" held a Conference with Mowlana Hazar Imam on 2nd May 1958, which was televised. 115 questions touching upon His personal life as well as His position as the 49th Imam of Ismailis. The picture gave an impression of a "QUIZ" and some of the answers given by Mowlana Hazir Imam throw considerable light on the principles of Ismailism and the belief of Ismailis.

========

Q. Your Highness, can I start by taking you back to what I think must have been the most momentous moment of your life, which was on the 12th July last year, when you were first told that you had inherited your grandfather's position. Now, what thoughts, truthfully, went through your mind at that moment ?

A. Well, it is rather hard to go through them all. I think the first one was the enormous responsibility which had come to me. I did not feel prepared for it. It was a very, very heavy burden to take over from a man of such status as my grandfather.

Q. Had you in fact known before that evening that you were going to carry this burden ?

A. No, I didn't. No, I had no idea about it at all.

Q. I wonder, do you know now, your Highness, whether or how long your grandfather had had you in mind, rather than anybody else in your family ?

A. I don't know. He had sent all the members of the family out to the Middle East. He had sent out Sadri; he had sent out my brother and myself. My father had been out there a lot and so I did not have any more idea than anyone else.

Q. But you transferred from civil engineering to studying Middle Eastern history didn't you ? That was earlier wasn't it ?

A. That was earlier than when I was nominated, oh! yes.

Q. Didn't that give you some inkling of what was in your grandfather's mind ?

A. No, because I chose the subject myself.

Q. Oh you did ! Why ?

A. Because it was a subject which interested me and because I had taken Islamic History at school before going to Harvard.

Q. Most people, I think, thought that Aly Khan would inherit the position. Have you been aware at all of any hurt feeling or feeling of disappointment on his part ?

A. I don't think so. I don't think my father would ever hold those sort of feelings towards me. I have never had the least impression of that.

Q. Looking back on it all now, are you left with the feeling that your grandfather or your grandfather and your father together were sort of preparing you with special training all your life for this?

A. No, I don't think so. To be quite frank I don't think so at all. I think that my father very much wanted me to see the community and see the way the community was run and so did my grandfather.

Q. You have had, haven't you, all your life, a pretty strict training in Islamic thoughts and principles?

A. Yes, that I have. Very much so.

Q. Could you detail your regime at all? Could you tell us how it happened?

A. Well, it began in East Africa with a private tutor in Islamic History and in the principles of Islam and then at school we had - that is my brother and myself had - a tutor also.

Q. A religious tutor?

A. A religious tutor and a tutor in history. And then, when I went to Harvard I took Oriental courses there too.

Q. Do you speak Persian yourself ?

A. No, I don't, no.

Q. Now, your being educated at Harvard which, of course, is a top ranking American university - did you have any say in the choice of this particular education? I mean, was there any possibility of your having gone to Oxford? Were you consulted at all?

A. No. My grandfather was very insistent that I should go to an American university.

Q. Did he say why?

A. Yes, he did. He wanted me to see what he considered the modern world and he wanted me to have as modern an education as he felt was possible. And I at first applied to M.I.T. and finally went to Harvard.

Q. But the thing about this is that your grandfather was always very - always often said that he ought to create a bridge between East and West. Now, in his time that meant creating a bridge roughly between Britain and the Middle East. Do you think the fact that you went to Harvard means that the bridge has changed, that it is now between the Middle East and America ?

A. I don't think so. It is very hard for me to discuss the reasons that my grandfather sent me to Harvard, but I think it was more that he wanted me to see the modern economic structure of the country and the pace of life. I think those were the things that really interested him. The scientific discoveries particularly.

Q. Do you like the pace of life?

A. Yes, I find it fascinating.

Q. Could you tell us now, in really quite simple language, exactly what your position is because I think all of us have a romantic idea of the spiritual leader in a great community, but is it for instance proper to compare you with the Pope?

A. No.

Q. Then with what?

A. Well because an Imam holds a religious position but he also guides the Ismailis when they ask for his guidance in secular matters, in business matters, health matters, even sometimes political matters.

Q. Supposing, for instance, one of your followers in a political trouble spot, let us say Kenya which is not after all impossible, were to write and ask you for political advice about how the community should behave there, would you feel in a position to give it ?

A. I would not feel in a position to give it, no. It would be the political committee which is organised to give advice on those particular problems that would give the answer. If it is a particularly sticky problem, then they would probably refer it to me.

Q. But on the personal, individual problems of groups or of people themselves, did you take up, as soon as possible after your grandfather's death this endless task, as I remember he described it, of constant advice and help to the community ?

A. Oh, definitely so.

Q. Do you do that every day yourself now ?

A. Yes.

Q. How many letters do you get a day on a sort of average roughly ?

A. It is hard to tell. It is the reports that are really the long things that one has to read. The reports from the various institutions.

Q. Yes, but do you get personal letters from members of your Community ?

A. Oh yes.

Q. Dozens a day or even more ?

A. It is hard to tell. If one is travelling then one gets an enormous number, because then they are in direct contact.

Q. When you are travelling do you ever feel very young and inadequate when you are facing a great crowd in some centre?

A. Well, it is hard to say because, after all, one has direct contact with the Ismailis, I mean after all, it is not as if it was a lot of people whom I did not know, or whom I had no contacts with at all.

Q. But you must be meeting great crowds for the first time, for example in Pakistan or in East AfricA.

A. It wasn't the first time. I had travelled before, you see, in those countries.

Q. Now this succession came, as you told us, as a bolt from the blue - tremendous, a thing which you hadn't expected. Have there been any moments since you succeeded when you have wished that perhaps this great responsibility hadn't fallen on you ?

A. No, quite frankly no.

Q. You have accepted that ?

A. Yes.

Q. Could you, if you wanted to, hand it over to anybody else ?

A. No.

Q. You couldn't ?

A. No.

Q. Have you designated your own successor? I am not asking you who, but have you in fact written a document anywhere naming your successor?

A. Well I have thought of that problem yes.

Q. Have you done it?

A. Yes I have.

Q. You have. Because, obviously, accidents could happen.

A. Well that is, of course, a very important factor in my own life.

Q. Yes. When your grandfather said, as he once did, that this was a job which could not be done until the death bed of the reigning Imam, you really would not agree with this with modern air travel and so on - you have to insure a bit more than that?

A. Well you would have to ensure that the successor was designated.

Q. So somebody in the world does know who your successor would be?

A. Yes. Myself.

Q. Only yourself ? You reached that decision entirely alone in other words?

A. Entirely alone.

Q. You have told nobody else?

A. I have told absolutely nobody else.

Q. We have been talking a good deal about your travelling. Could you perhaps let us know where, geographically about the world, the community is now dispersed, as you are a pretty dispersed community?

A. I couldn't go through it in detail. The large communities are in East Africa, Pakistan, India, Persia, Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Malaya, Burma, Belgian Congo, Mozambique, South Africa, Madagascar. It is a very, very dispersed community.

Q. And how many are there altogether ?

A. I don't know myself.

Q. I think there is a lot of misconception perhaps about this business of the Aga Khan being weighed against precious stones. Am I not right in thinking that this, in point of fact, is for charity?

A. That is correct. It is entirely a symbolical ceremony and the funds were used by my grandfather either to build an investment company or lending company or something like that.

Q. Now could I ask a rather important question here because reading the circumstances of your grandfather's death, it seemed that his fortune was not left to you. It was left partly to your step-grandmother and partly to your father in the customary way. Does this mean that you are not able to control the funds of the Imamat yourself ?

A. No, because my grandfather left, according to the Shia law, his secular property to the heirs but the Imamat property stays with the actual position of Imam.

Q. So that you are not obliged to ask either your father or your step-grandmother before you can take a financial step in the Imamat?

A. No, because the Imamat property is something which the Imam controls.

Q. You control that yourself ?

A. Yes. The Imam controls it himself.

Q. It is very difficult to assess the actual value of all that property isn't it?

A. Practically impossible.

Q. Apart from the sort of wild dreams that have been made about it, are there any sort of ways one could reach any estimate of it ?

A. No, because the properties are changing the whole time. The schools are being built and sold, hospitals are being built and sold, the community is moving the whole time.

Q. Well let us put it this way. Your grandfather was often called one of the richest man in the world. Was that true?

A. I don't think so.

Q. Is it true of you ?

A. No, I don't think so either.

Q. And that's as close as you can come on that ?

A. As close as I can come.

Q. Tell us how this money is collected? I mean is it a system of taxation or is it really entirely voluntary?

A. No - it is entirely voluntary and the Imam uses the money either to grant scholarships to students, to grant capital to a school or a hospital. We have got one hospital in Nairobi at the moment which will have cost about 400,000 pounds and my grandfather gave a very large sum to that hospital.

Q. Is that confined to your community or is it open to all ?

A. No, that is open to all the communities.

Q. Could you tell me, your grandfather and his grandfather before him, by the accident of history settled, or your great, great-grandfather settled in IndiA. Is it in your mind, as I think without presumption I may suggest it was in your grandfather's, that the body of your community is moving elsewhere. Is it going to East Africa?

A. I don't know what my grandfather's ideas were on that subject. That was not something he had spoken to me about. I don't think very many of the Ismailis are moving from India to East Africa at the moment. That was a process which happened some time ago.

Q. But you yourself have been crowned in East AfricA. Do you have great interests, both secular and sacred there?

A. Yes, definitely.

Q. Here you have this fantastic responsibility and there is a great deal of money knocking about, whether you are the richest man in the world or not; now who actually looks after all this? I mean, you are taking a university course, a demanding one. How much time a day do you pay attention, do you give to these affairs ?

A. A lot of time and above all one has to sort out the problems which are really important and which take a lot of, how should I say, advice.

Q. You take advice?

A. Yes, definitely. I take advice from wherever I can get it.

Q. But have you got a regular sort of appointment of advisers?

A. Yes I have a staff.

Q. But yours is the responsibility.

A. Completely.

Q. You were talking about the important things in your daily life. Now I think there are some things that are not quite so important. I am wondering do you ever get bored when you go around schools and hospitals one after the other, thousand at a time?

A. No, not at all, not at all. Because the curriculum of the school changes in every country and it is very interesting to see the way the children of the various countries react to the different curriculums which they have and one is always having to bring up the education to modern standards, otherwise the children get very bored with their schooling.

Q. I hope you won't misunderstand the question if I ask whether this job really can be done without a wife.

A. I am not married so I can't tell you.

Q. No, but would you not feel the need of a wife, because in all seriousness, there are surely a great many social jobs which come easily to a woman and your grandfather certainly depended a great deal...

A. Well, there are certainly some social jobs which I am not very happy doing. Kissing babies, for instance!

Q. Do you rely much on the advice of your grandfather's widow?

A. Yes I do on the major issues. She has always given me very good advice.

Q. Is it true that your grandfather did suggest in his will that you should turn to her for advice on major issues?

A. Yes, he did.

Q. Well, I wanted to ask you, am I right in thinking first of all that on the whole, in the Muslim world, women are not usually encouraged to take leading positions in affairs and does this indicate any significant change of view on your grandfather's part ?

A. No, I don't think so. I really do not think that in the least, but I think my grandfather considered her a person who knew the community very well indeed and therefore any important problems her advice was obviously very worthy. So is my father's, he has travelled a great deal in those countries.

Q. While we are still on the question of wives, you are married off by the papers about three times a week. Do you feel that you are fairly reported in these matters? Are you fairly reported on your social life and so on?

A. No, no.

Q. You don't think you are?

A. I think that one can't lump the press together. It is rather unfair. I think some papers give one a beating and others don't.

Q. But you have got used to living in a pretty constant glare of publicity.

A. Now, yes.

Q. You take it as it comes.

A. Well there is not much one can do about it.

Q. If you had a free choice now, where you would settle and live, which country would you choose?

A. That is a very difficult question to answer because for the moment I have been travelling for the last 6 1/2 months. I will still be travelling, and the big decision now is whether I go back to Harvard, so that question does not really arise in the near future.

Q. Is it at all practical for you to go back to your studies at Harvard with this tremendous new responsibility you have got?

A. I think so. I think so. I think that Harvard would give me very good preparation in the various fields which are important.

Q. You would then have to do something to appoint a regular staff to advise you in political matters presumably?

A. No, because you have councils you see, who guide the community on the issues and people who are either in government service at the time, people who know the whole frame of the political set-up.

Q. And you keep in touch with them yourself directly?

A. Oh yes. I have regular reports from them.

Q. I don't understand why Harvard at all - I mean, you are studying Middle Eastern history and so on there. Now isn't that rather like the King of England studying English history in Bangkok?

A. I don't think so. Harvard has got a very, very fine set of Oriental scholars. A very, very fine set.

Q. You mean the best in the world perhaps?

A. That I wouldn't say. I don't know what the other universities have, but I know that Harvard has got a very fine set of...

Q. But they are in fact Christian, aren't they?

A. Most of them are Christian. Some of the visiting professors are Muslims.

Q. Isn't that bound to slant their view of Middle Eastern history, especially early history?

A. It might do.

Q. And who corrects that? Yourself?

A. Well, it is very hard, if you are under the influence of a professor, to know whether his view is strongly slanted or not unless you come in contact with some other professor whose view is along another line.

Q. One of the most fascinating things about your grandfather was that while he was this great religious leader he also, in the public eye in the Western world, was a man who had a great many pleasures and took them with splendid ease. Are you going to carry on that tradition at all?

A. I don't know. I haven't been Aga Khan long enough to tell. It is only since July, and that is some eight months.

Q. But he was a great figure of the race track wasn't he? Colourful, what we call a sport. Now, did he never show any disappointment that you signally - I think I am right in saying - are not interested in racing and horses?

A. Well no, that he never did, because he was very, very wide-minded about that. If one had other interests than his own, they were really his interests when you spoke to him.

Q. You row I think?

A. Yes, I did rowing. And he would always ask... the first question he would ask was...how your particular sport was coming along, not whether you were doing his sport.

Q. I hope you appreciate that the rowing world could do with a patron. Yes if you could get four winners... like the famous four Derby winners. And you also have all sorts of other private things. For example, you play the mouth organ. Is that right?

A. Well I tried it. I can't say I played it.

Q. But you are really rather keen aren't you?

A. Well I enjoy it, yes. I am a great admirer of Larry Adler.

Q. Are you interested in music generally

A. Yes I am.

Q. What particular tastes? Are you a cat or not?

A. No.

Q. A square, are you?

A. No, neither.

Q. You like classical music on the whole?

A. Very much.

Q. How do you feel about the whole question of night-clubbing and cha-cha-cha and mambo and so on? How do you stand all that stuff?

A. Well I don't stand in it at all. Why should I stand in it?

Q. But you do occasionally go don't you?

A. Yes, I occasionally go with friends of mine if they have a party and after a theatre or something they want to go to a night club.

Q. But you don't particularly like it?

A. Not particularly. I mean, I certainly wouldn't spend every night of my life in a night club.

Q. Are you interested in the theatre and ballet?

A. Very much indeed. My grandfather always took us to the ballet a great deal.

Q. He loved ballet. I remember him in Venice, the ballet there, it was an American ballet. He adored it.

A. Absolutely adored it.

Q. Have you had much chance to get to the New York theatre while you have been at

Harvard?

A. Very little.

Q. And in London? Have you been now on this visit?

A. Not on this visit. I haven't been here long enough. I have only been here two or three days each time.

Q. Yes, I see. Do you find that as a consequence of the fantastic and fabulous position you hold that there are these rather tiresome consequences such as fan mail, mash-notes from young women.

A. Not very many, no.

Q. Do you ever find people asking you cheeky questions about religion and so in the course of the day? Asking you rather embarrassing questions about Mohammed and so on?

A. Well they are not cheeky questions. They are usually questions of people who are interested. One could not qualify them as cheeky questions.

Q. You don't ever have anyone one sort of buttonholing you and trying to convert you to the ...or something?

A. Well, sometimes they do, but then a general answer is usually quite sufficient.

Q. There is one question I would like to ask you on this... it is a difficult one. You see, I think the Muslim religion encourages people to enjoy life to the utmost, and this your grandfather certainly did and indeed your father does too, but have you ever found it an embarrassment to you in the months you have been doing your present job, this reputation for good living that both your grandfather and your father enjoyed but which in a way I think you don't share?

A. No, I don't think so, because the community in general treat you as a single person. They don't attach any of the ideas which your family have had to yourself and they always treat you s their Imam

Q. You are already a total individual yourself when you are Imam?

A. Well, one is in fact the Imam which is the centre of the organisation.

Q. Putting it the other way round, the fact that you do not frequent racetracks, will that rebound to your credit among your followers?

A. That I don't know. I never ask them. I don't know at all.

Q. Have you had a feeling in the tour that you have made so far that you are comparatively little-known among your followers. Did your appointment, in other words, occasion surprise among your own community?

A. I don't know. It would be hard for me to find out but I really couldn't answer that question because I am not qualified to answer it. I don't know.

Q Am I right in thinking that one community did in fact declare your father was the Imam?

A. It was more a question of timing. They declared that before the actual nomination had been made.

Q. It was just a pure mistake?

A. There was a delay between My grand-father's death and My nomination and it was in that particular period that they nominated My father.

Q. You have been to Pakistan haven't you?

A. Yes, I have.

Q. Have you been to India yet?

A. Yes I have also.

Q. Does your family still own and you own a lot of property in Bombay?

A. Not a lot of property. We own one family house which has been the traditional family house since My family went to IndiA.

Q. Are you going to keep that on?

A. I think so. It certainly will stay in the family. I don't know whether it will be My house. It might be My father's.

Q. Yes, but you are intending to keep it on are you?

A. Oh! Yes.

Q. And you've done India, Pakistan, East Africa, and you are now going to the Congo?

A. Yes, Belgian Congo, Mozambique, South Africa and Madagascar.

Q. How do you stand up to that sort of travel?

A. It is tiring but the interest is quite sufficient to keep you going.

Q. You got that from your Grandfather?

A. Yes.

Q. When Harvard is over, your life will be one of almost constant travel?

A. I don't know. If I go back to Harvard it will give Me a little bit more time to sort of plan my life. For the moment it has been difficult because of the travelling I have had to do.

Q. One of the things your grandfather did most successfully, as John Connell said a minute or two ago, was to construct some sort of bridge between East and West. Now, he was clearly Asian in many of his ways, although he was a British citizen, and knew this country well, but looking at you, and talking to you now, I cannot help feeling that you are almost entirely Western. Now, I wonder if you are in a position, therefore, to go on with this work or whether it may not be necessary for you to move yourself to Asia to do it so successfully?

A. No, I think that is an incorrect view because an Asian or at least a person of Asian origin and a Muslim can very well be educated in the West and can lead a normal life in the Wet and yet he remains just as Muslim and just as Asian fundamentally as if he had been educated there.

Q. Do you find your deep affinities are with the Islamic peoples rather than to Western.

A. Very definitely so.

Q. But wasn't there a question some time that you would eventually settle in the Middle East?

A. No, that was a question of My going to the University in the Middle East.

Q. And you may still do that?

A. Well, I had intended to before I became Aga Khan - yes. I intended to go to the American University in Beirut for a year.

Q. From the way your Grandfather settled in the South of France, do you have any place in mind where you will make your centre?

A. No, I think he settled there mainly because at the end of his life, he wasn't to travel a great deal. He was a sick man and couldn't support those sort of journeys.

Q. You will go on living out of a suitcase for years and years, will you?

A. Well, certainly until I decide whether to go back to Harvard, yes.

Q. How many languages in fact do you speak altogether?

A. Two, I think relatively fluently, English and French, and a smattering of Urdu, a smattering of Spanish and a little bit of Italian.

Q. Yes, I see, but you don't speak a wide variety of Asian or African languages?

A. No, I don't.

Q. You have a younger brother than yourself? Is he going to take any of the burden off your shoulder or not?

A. I don't think so. You see, the role does not have anything to do with My brother. He will probably form his own life when he has finished at Harvard.

Q. Does the fact that you have been to Harvard mean that you have ideas for modernising.

A. Secular institutions yes. Definitely so.

Q. You have definite views on...

A. Well, on banking systems, on those sort of things .. if one has the chance to study them, and one finds that they work better ... what My grandfather did was to try and put them onto a working basis in the community.

Q. Am I right in thinking you have also made adjustments in the method of prayer to the Koran?

A. No, I am afraid not.

Q. Quite untrue is it?

A. That was quite untrue. The comment I made there was that very young children - children of the age of 2 or 3 - were not to stay up late at night for the last prayer - or sick people. That was the only comment I made.

Q. Just talking a little bit about modernisation - how much do you think a community can take modernisation? Will it not crack apart completely if you give it too many shocks?

A. No, I don't think so. I think they are a very sensitive people and quite capable to live a modern life and yet keep the faith which characterises them and that was certainly one of the great achievements of My Grandfather.

Q. The studio clock tells me we've come to the time when I have got to put the last question to you and I have been thinking as you have been talking of remarks which your Grandfather made when he appeared in this programme four years ago and he said that he wasn't a painter and he wasn't a sculptor and so the idea of creation came to him in the breeding of horses and the breeding of flowers. Now, what gives you this personal sense of creative satisfaction in life.

A. Well, that is very hard to say. I think it is the sense of being able to mould people, to mould their lives, to help them in the various ways that one can whether it be secular ways or even religious ways. I think Middle Eastern communities have a big problem. They have their religion and they have the modern way of life which they are trying to pick up and to Me that poses a big problem for them to solve.

- 11797 reads

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.

Ismaili.NET - Heritage F.I.E.L.D.